[Here's a two-sentence review of this piece: "Come for the history. Stay for the story." As Virginia's granddaughter, I am biased. But hopefully your assessment will match up with mine! Read on. . .]

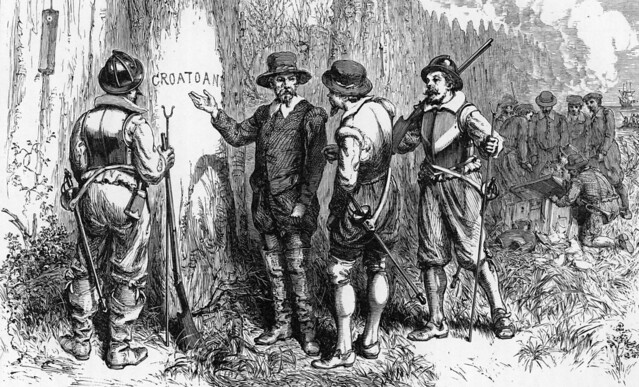

"The Lost Colony" sounds

like "The Lost Atlantis," a myth or perhaps a ghost story, but North

Carolinians cherish their history of being the first port of entry,

thirty-three years before the Pilgrims famously landed on Plymouth Rock.

These first colonists

came in 1587 to Roanoke Island just off the North Carolina coast and apparently

were established when their ship set sail again for England to bring supplies

and more colonists. Four years later when the ship returned, the settlers had

vanished, and the only clue as to what became of them was the single word "Croatoan"

carved into a tree.

A pageant called "The

Lost Colony" is produced yearly near the coastal town of Edenton, and the

setting is constructed of materials that came easily to hand for the settlers,

who stripped young trees into poles which they lined up for fences.

These enclosures are

similar to the grape stake fences which screen off small gardens of another

early settlement, Georgetown. There houses are built flush with the cobbled

streets and lack the porches or veranda popular in the lower South, where "garden"

refers to the growing of vegetables and other areas surrounding a house are

called yards.

Mrs. Dunlap's son Duncan,

enamored of his fiancée, was also enamored of her family's house in one of

these stylish Georgetown neighborhoods with just such grape stake fencing. When

his mother was planning her new house as close as possible to Papa's house and yard,

Duncan ordered architect's plans for her in a style which if not as grand as

the Georgetown houses were at least distinctive, even peculiar, for the street

we lived on where every house, large or small, was introduced by a porch. The

plans stated that the style was Dutch Colonial; and when it was almost

finished, the Railway Express truck delivered another package from Duncan of a

size and shape puzzling to the Railway Express Agent, to the driver, and to all

those who watched him load and unload.

The house plans Duncan

sent ignored Mrs. Dunlap's need for a garage, which Duncan claimed was an

anachronism anyway, thus creating a lively discussion when Mrs. Dunlap passed

on his comment after looking the word up before going to The Book Review Group.

Duncan's ongoing effort

to educate his mother to the level he had attained through seven years of

higher education included his frequent use of words such as anachronism

with accompanying instruction. Contrary to what one might expect, his mother

enjoyed these lessons and practiced what she learned on her neighbors,

especially my mother, and on other members of The Book Review Group. There was

sometimes a certain nervousness about her conversation, a studied manner in

which she would say, "That reminds me" when the prior connection was either

faint or nonexistent, and the listener was surprised by a discourse alien to

Mrs. Dunlap's usual downhome manner.

"Duncan means well, I

suppose," my mother said, "But he's trying to make a silk purse out of a sow's

ear," blushing with embarrassment the minute she realized what she had said. "Of

course, I don't mean that the way it sounds."

The garage that Mrs.

Dunlap's contractor, who claimed he did not need any particular plans, put up

for her was lacking in aesthetic appeal; but the lot being so small and the

house being so large for the lot, the main problem was that the garage and the

clothes line were necessarily placed in the only available space remaining and

stuck out like two sore thumbs.

Duncan, soon to be

married, doubtless wanted his mother's house when he brought his future bride

to meet her to look as attractive as possible, perhaps to look as non

small-town Southern as possible without his seeming to express disloyalty to

his upbringing. If Mr. Dunlap, Sr., had lived long enough to experience this

phase of Duncan's ambivalence towards his hometown, he might have encouraged

Mrs. Dunlap to be less malleable; but as it was, Mrs. Dunlap was pretty much

putty in Duncan's hands. Mr. Dunlap, Sr., for instance, like Papa, had been opposed

to new-fangled conveniences of all kinds and refused to get into a bathtub,

citing with dramatic flourishes that the one time he tried it he slipped and

nearly broke his neck. He would doubtless have been shocked to learn that

Duncan had talked Mrs. Dunlap into having two bedrooms upstairs, one with a

stall shower, the first such arrangement in the memory of her contractor, as

well as a basement with furnace for central heating.

Papa's house, by

contrast, only recently had been modernized to the extent of installing thermostat-controlled

oil-burning stoves to replace the old cast iron wood-burning stoves.

Unfortunately, the oil barrels were installed on Mrs. Dunlap's side of the

house and were unsightly to say the least, but in no way an aesthetic irritant

to Papa, who stayed indoors in bad weather and otherwise sat on the front porch

where he avoided seeing Mrs. Dunlap's house altogether. His former brisk walk

uptown, his daily constitutional, had been reduced by the infirmities of age to

puttering around in the back yard when the weather was nice.

It was soon after Duncan

and his fiancée announced their engagement to Mrs. Dunlap that the Railway Express

truck drove through our backyard (not everyone knew how keenly Papa resented

that liberty) right up to Mrs. Dunlap's kitchen door and unloaded the bundle of

grape stakes.

[First third of an undated story by Virginia McKinnon Mann. Click here for the second installment. Roanoke illustration via State Archives of North Carolina.]

No comments :

Post a Comment

Comments are welcome!