[The

first and

second installments have already been posted. You may recall that Papa just said to Mr. Benton, the carpenter, "Those poles are illegally trespassing on my property." What happened next was. . .]

Mr. Benton, who never

expected the fence to get put up in the first place, apologized and moved his

posthole digger and the sawhorse before taking the poles back to Mrs. Dunlap's

garage.

Then he waited for Mrs.

Dunlap to return from wherever she had gone and sat down to think why she would

want a fence like that anyway. It was while he was sitting on her kitchen steps

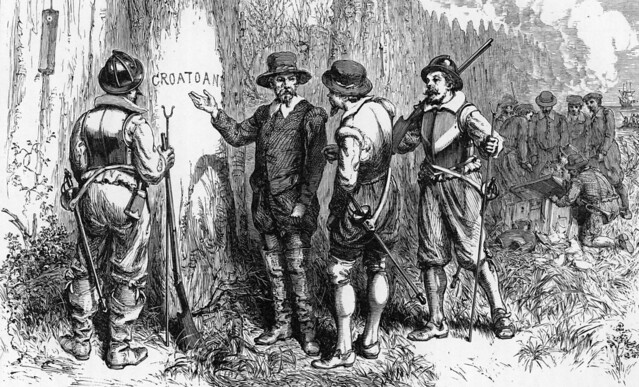

looking intently at the grape stakes that it came to him how much they reminded

him of "The Lost Colony." He had taken his family two years ago to see the pageant,

and he had found every part of the experience interesting.

"It would be better, Mrs.

Dunlap," he said when she finally came home from The Book Review Club, "For you

to have a kind of Tom Sawyer fence, you know, wide boards and painted white. I'd

advise using house paint, lasts better than whitewash. Tom Sawyer was just a

story, but the fence went with his Aunt Polly's house; and these Lost Colony

poles don't go with your house, not a bit of it."

Mrs. Dunlap was not at

all interested in Mr. Benton's decorating ideas, for she long ago accepted

Duncan's pronouncements as the final word. Or as one member of The Book Review

Club said after hearing Mrs. Dunlap recount Duncan's opinions on architecture,

"The Oracle hath spoken."

Mrs. Dunlap could guess without

even asking Mr. Benton why the grape stakes were back on her property, but Mr.

Benton told her anyway.

"Mr. Huntley said those

poles were trespassing on his property. Illegally trespassing is what he

said."

"When he sees how nice

and natural my fence looks, he'll be begging me to put one up on his side to

hide those unsightly oil barrels," Mrs. Dunlap said in a just-you-wait-and-see

kind of voice.

Mr. Benton kept quiet.

After all, he could not force her to take his advice. He showed her where he

thought the post holes should go if she was determined to have a Lost Colony

fence, but he could not help mentioning that it might be bad luck considering

what happened to those poor colonists. Duncan would come to see his mother and

all that would be left would be one word carved on her pecan tree, "Croatoan,"

the meaning of which not one single person in the whole wide world knew.

"That's the silliest

thing I ever heard of," Mrs. Dunlap said, but decided to wait to hear what my

mother had to report after her talk with Papa.

It was a little like "The

Emperor's New Clothes," Mr. Benton told his wife when he got home. Mrs. Dunlap

thought the fence was high style for no reason other than Duncan telling her it

was, and. anybody could see it was no style at all. He also told the folks at

the hardware store that Mrs. Dunlap wanted him to build a Lost Colony fence,

and pretty soon every car in town slowed down to take a look. Mrs. Dunlap never

doubted for a moment that they were all looks of pure envy. Although no one

asked her how they too could order grape stakes for fencing, she volunteered

when she went to Ann's Beauty Shoppe to have her weekly shampoo and set that

they were a special order from her son Duncan, who had been charmed by their

naturalistic style while visiting his bride-to-be in Georgetown, District of

Columbia, the Nation's Capital.

The next day when Mr.

Benton came to work he tried to persuade Mrs. Dunlap if she was determined to

go ahead with the job to use leather strips to lash the poles together. He

explained that he actually had seen "The Lost Colony" and that he had examined

the way they constructed their enclosures. "It will look very natural, Mrs. Dunlap,

if that is what you are after."

"What I'm after is making

my side yard look more presentable so a person coming to visit won't be looking

straight into my garage."

"You might have run your

driveway on the other side of your house," Mr. Benton said, "But I guess it's

too late to cry over spilt milk. Tell me again, Mrs. Dunlap, what the name of

your house style is."

"Dutch Colonial," she

said. "Duncan sent me the house plans, and he also sent me the grape stakes."

Mr. Benton, who already

knew that Duncan had exerted what he considered undue influence on his mother,

was planning to say that he was pretty sure the Railway Express people would

come pick up the grape stakes and send them right back to wherever they had

come from; but just then my mother came out to tell Mrs. Dunlap that she had

not been able to persuade Papa to let the grape stakes be used. She was trying

to use any but "obscure" not wanting to hurt Mrs. Dunlap's feelings, but in her

concern not to make fun of Mrs. Dunlap she said "congeal" instead of "conceal"

and had to ask for a glass of water before she could get out what was the

honest truth: Papa did not wish for Mrs. Dunlap to beautify his property, no

matter how earnest she was in her wish to do so.

The next day Mrs. Dunlap

took Mr. Benton's suggestion to place all twelve poles in a kind of rippling

arrangement just past her kitchen door, partly hiding the garage and her clothes

line, providing a backdrop for the bushes that were already planted and growing

well. "That way," he said, "It won't look near so much like 'The Lost Colony.'"

Mrs. Dunlap laughed. "I

certainly don't want to look like 'The Lost Colony,' not even for Duncan and

his bride."

"And there won't be any

ghosts lurking around," Mr. Benton added, but Mrs. Dunlap was already thinking

about something else.

Surprising to all

concerned, Duncan was pleased with Mr. Benton's arrangement, which he

pronounced "serpentine" and reminiscent of the brick walls Thomas Jefferson

designed for the University of Virginia.

"I can live with that,"

Mr. Benton said; and Mrs. Dunlap smiled with naturalistic pleasure.

[The end! Undated story by Virginia McKinnon Mann. I think the moral is that we all ought to run out and get some grape stakes. Ha!]

![Harold Kantner Special Collection Photo [Photo]](http://farm7.staticflickr.com/6096/6335809400_5ae1114236_z.jpg)